박미나가 학부 시절인 1998년부터 꾸준히 지속해 오고 있는 〈색칠 공부 드로잉〉 연작은 미취학 아동을 대상으로 도형, 숫자, 알파벳 등 기초적인 규칙과 언어를 알려주는 색칠 공부에서 출발한 작품이다. 색칠 공부는 물감이나 크레파스 등을 이용하여 색으로 그림을 채우는 놀이로 생각하기 쉬우나, 그림 속 면을 구획하는 윤곽선과 명료한 형태들에서 유추할 수 있듯이 교육적인 목적을 가지고 있다. 구획된 경계의 선을 넘지 않거나, 비워진 면을 채워 완성의 형태를 만들어야 한다는 색칠 공부 내 가르침은 틀에 박힌 이해와 완성을 유도한다. 박미나는 색칠 공부 교본이 제시하는 지시문을 따르지 않고 주관적인 반응을 토대로 한 변주를 시도한다. 색칠할 때 주로 쓰이는 색연필, 펜, 물감뿐만 아니라 마스킹테이프, 스티커, 도장 등 여러 재료를 활용하며 교본 속 선이나 형태를 가리거나 변형시킨다. 이처럼 작가는 지시문의 완성을 위한 공부가 아닌 놀이로서 드로잉을 수행하며, 색칠 공부를 통한 개념 습득의 인습적인 측면에 질문한다.

박미나가 2007년부터 진행해 오고 있는 ‘딩뱃(Dingbat) 회화’ 연작은 그래픽 디자이너들이 고안한 이미지 문자인 ‘딩뱃’을 가지고 문자와 이미지의 관계를 실험한 작품이다. 컴퓨터에 문자를 입력한 후 이를 딩뱃 폰트로 설정하면 여러 이미지가 암호처럼 나열된다. 언어인 문자가 이미지란 기호로 전치되는 것이다. 이처럼 딩뱃은 언어와 또 다른 약속으로 문자와 이미지를 연결한다. 하나의 문자와 하나의 이미지가 어떤 논리와 이유로 연결된 것인지 정확하게 알 수 없지만, 언어로서 디지털 인터페이스에서 유효하게 작동한다. 주어진 약속으로 제시되는 딩뱃을 작가는 가져와 자신의 상상을 담아 크기나 배열을 조정하고 색을 더하여 회화로 그려낸다. 이렇게 재조정된 딩뱃은 본래의 약속과 의미에서 벗어나 여러 이야기를 담을 수 있는 상상의 요소로서 회화에 담긴다. 박미나의 ‘딩뱃 회화’ 연작은 보는 이의 상상력과 해석이 더해져 문자와 이미지의 유기적인 관계를 극대화한다.

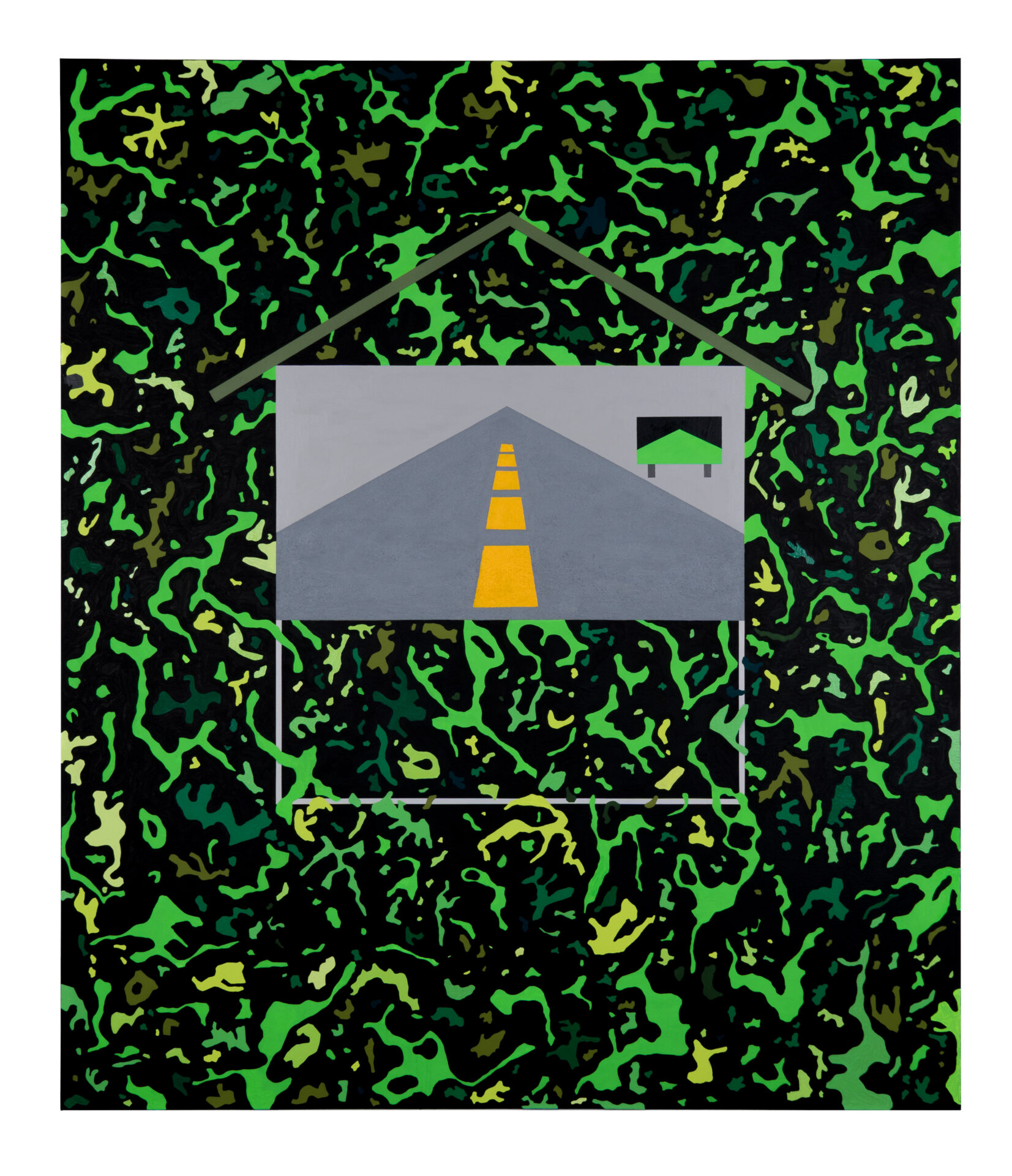

〈벌집〉은 2023년 국내 시중에서 유통되고 판매된 물감 브랜드 3사의 아크릴 물감 세트를 재료 삼아 그린 작품이다. 작가는 24색 혹은 36색 물감 세트에 포함된 개별 색들을 펼쳐놓고 한 면에 한 색만을 사용하여 칠했다. 색으로 완성된 면들은 색의 차이 혹은 경계로 인해 육각형의 형상을 갖게 되고, 여러 육각형은 한 화면에 모여 거대한 벌집을 이룬다. 작가는 이러한 작업 과정을 통해, 물감 세트의 가려진 이야기를 드러낸다. 각 물감 회사는 자신들이 생산하는 무수한 색 중 몇 개만을 추려 물감 세트를 구성하고 이를 판매한다. 물감 세트의 유통과 소비의 순환은 그 시기의 문화와 취향이 반영된 결과처럼 보이나, 한편으론 물감 회사가 제시하는 대표적 색에 맞춰 우리의 취향이 좌지우지될 수 있는 위험을 내포하고 있다. 이러한 물감 세트를 둘러싼 사회적, 문화적 문제는 박미나의 또 다른 작품 〈세트 컬러〉 연작에서 더 전면적으로 다뤄지고 있으며, 본 전시에 소개된 〈벌집〉은 〈세트 컬러〉 연장 선상에서 ‘집’을 소재로 거시적 체제가 미시적 개인에게 미치는 영향을 심도가 있게 담아냈다.

박미나의 작업에서 자주 등장하는 ‘집’이란 소재는 그의 작업 세계를 관통하는 주요한 이야기를 가지고 온다. 집은 개인과 밀접하게 연결되어 삶의 방식과 환경에 영향을 미친다. 누군가에겐 사적인 공간이면서 동시에 가족과 같은 공동체의 근거지가 되기도 하는 집은 누구나 공감할 수 있는 공간의 기억을 제공한다. 작가는 이러한 집에 주목하여, 집을 중심으로 일어나는 사회적, 문화적 영향과 그로 인해 축적되는 개인의 가치관이나 취향을 살핀다. 작가는 집을 이질적인 요소로 결합하거나 해체하는 등 다양한 방식으로 그려내는데, 이는 단순한 형식적 실험을 넘어 시대의 상으로서 집을 둘러싼 고정관념과 욕망의 이면을 드러낸다. 이처럼 박미나는 집을 통해 사회와 개인의 관계를 반추하며 시각의 지평을 넓힌다.

MeeNa Park’s Drawings, a series she has continued since her undergraduate years in 1998, take inspiration from coloring books designed to teach preschool children basic concepts such as shapes, numbers, and the alphabet. Often seen as a simple activity of filling in pictures with crayons or paint, these books serve a pedagogical purpose, as evidenced by the clear outlines and neatly segmented forms that structure each page. Within this framework, children are guided to stay within the lines and fill the empty spaces—an approach that encourages fixed ideas of completion and standardized understanding. Park subverts this didactic mode by introducing her own subjective interventions. She uses not only colored pencils, pens, and paints, but also masking tape, stickers, and stamps to conceal or transform the given lines and shapes. By treating coloring not as an exercise in instruction but as a form of play, she challenges the conventional methods of concept acquisition and invites us to rethink how learning can take place outside the boundaries of prescriptive guidance.

MeeNa Park’s ‘Dingbat Painting’ series, which she has been developing since 2007, experiments with the relationship between text and image using ‘dingbats’—pictographic characters created by graphic designers. When standard text is typed on a computer and set to a dingbat font, it transforms into a string of symbols that resemble a secret code—a process that displaces written language into visual form. In this way, dingbats establish an alternative convention, linking letters and images not through logical reasoning but through an arbitrary system that nonetheless functions within digital communication. Park takes these pre-set forms and reinterprets them in her paintings by adjusting their scale and arrangement, adding color, and infusing them with her own imagination. Freed from their original codes and meanings, these reimagined dingbats become vessels of multiple narratives—elements of imaginative possibility. The ‘Dingbat Painting’ series amplifies the organic interplay between text and image, drawing on the viewer’s interpretation to complete its meaning.

Beehive House, part of MeeNa Park’s ‘House’ series, was created using acrylic paint sets from three brands that were widely distributed and sold in Korea in 2023. The artist laid out the individual colors from each set—typically composed of 24 or 36 colors—and painted each surface using only one color. As a result, the painted surfaces take on hexagonal shapes, formed by subtle differences and boundaries between colors, and these hexagons come together on a single canvas to form a massive beehive. Through this working process, Park reveals the hidden narrative embedded in commercial paint sets. Each paint company selects only a handful of hues from the countless colors it produces to compose its sets. While the circulation and consumption of these sets may appear to reflect the cultural tastes of the time, they also carry the risk of shaping our preferences according to the ‘representative’ colors chosen by manufacturers. These socio-cultural issues surrounding paint sets are more directly addressed in Park’s Set Colors series. On view in the exhibition, Beehive House extends that line of inquiry by using the motif of a ‘house’ to examine how macro systems exert subtle yet profound influence over individuals on a micro level.

The motif of the ‘house,’ which frequently appears in MeeNa Park’s work, carries a central narrative that runs through her artistic practice. A house, intimately connected to the individual, shapes both ways of living and the environments we inhabit. For some, it is a private space; for others, it serves as a foundation for communities like families—offering spatial memories that many can relate to. Park focuses on this dual nature of the house to examine the social and cultural forces that unfold in and around it, and how they accumulate to shape personal values and preferences. She depicts houses in diverse ways—combining them with heterogeneous elements or deconstructing them—not merely as a formal experiment, but as a way to reveal the underlying assumptions and desires embedded in the image of the house as a symbol of its time. Through this approach, Park reflects on the relationship between society and the individual, expanding the horizon of visual perception.